The Stone Carver's Story

Our prize winning entry in the National Archive Competition, 20sStreets

Joseph Cribb is standing on the far right alongside his wife, Agnes.

Great Dunmow War Memorial

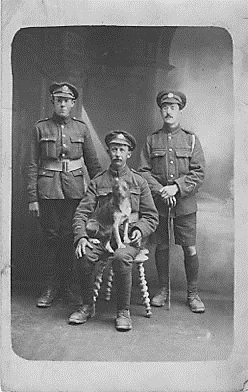

Joseph Cribb (right) with his brothers

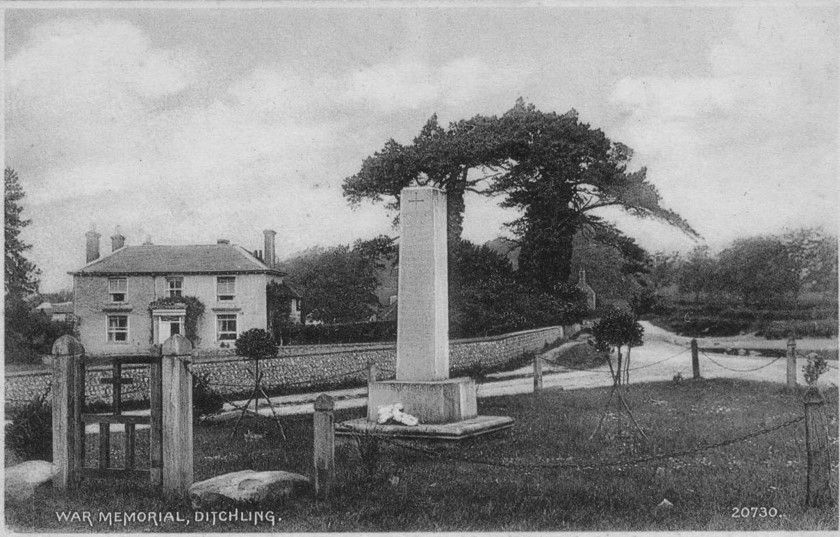

Ditchling War Memorial

The Stone Carver's Story

Ditchling History Project has previously researched many aspects of the First World War and its impact on the village. In 2003 we held an exhibition, Memories of War at Ditchling Museum out of which came two books – ‘Memories of War’ and ‘For the Fallen’ telling the stories of our war memorial and the men listed on it. In 2014 and again in 2018 research concentrated on the First World War. In 2014 ‘Our War Stories’ collected family stories from the community and in 1918 a trail around the village, ‘Street by Street’, explored the contributions made on the home-front as well as the lives of the men who went to war and those who did not return. Now, using the 1921 census, we can place not only the men who came home to their families but also, sadly, the widows and children of those named on the village war memorial. This is the story of Joseph Cribb, the local craftsman who carved twenty names of those Ditchling men who would almost certainly have been known to him.

The Sussex village of Ditchling lies beneath the South downs, historically a farming community, it has become known from the early part of the 20th century for the artists and craftsmen who settled here. The most famous, in some respects infamous, was the sculptor Eric Gill who in 1907 brought his family to the village from London and with them his sixteen-year-old apprentice, Joseph Cribb. The 1911 census shows Joseph still living at the Gill family home in the village High Street. Two years later, his apprenticeship ended, he was trusted to work on his own on such important commissions as Oscar Wilde’s tomb in Paris, which must have been quite an adventure. In the same year following Gill’s example, he was received into the Catholic church.

Born in Hammersmith in 1892, Joseph settled into country life. He developed a passion for fishing and began a lifelong interest in the natural world becoming an expert on butterflies and beetles.

However, the war came and the stone carver and countryman turned soldier on the Somme. He joined the Royal Sussex Regiment as a forward bombardier and in October 1916 was wounded in both legs while taking a German trench. In the notebook he carried with him he writes of lying in the trench for four days ‘with 5 or 6 other Sussex fellows’ surviving on the provisions the Germans had left behind before being relieved and brought home, first to the Eastern General Hospital in Hove and then to a convalescent home in Eastbourne.

When declared fit, Joseph underwent a short period of training before returning to France in February 1917. His diary records that he spent over two months in the line until, on the night of April 27th 1917, he arrived at camp outside Poperinghe before taking a train to St Omer via Hazebrouk and then marching ‘through beautiful countryside’ to the village of Acquin for a fortnight’s rest. It is no surprise that he describes the wild flowers he saw on the way - ‘celandines, periwinkle and dandelions on the roadside and the hawthorn hedges and elderberry trees in full bloom.’

As the war came to an end, Joseph was working with the Royal Engineers pegging out cemeteries in the Somme area. The Imperial (later Commonwealth) War Graves Commission was established at the instigation of Fabian Ware who was so saddened by the sheer number of casualties that he felt the dead must not be lost forever. When Eric Gill’s younger brother MacDonald (Max) was appointed designer of the lettering on the IWGC headstones, he turned to Joseph to assist him.

In 1917 Joseph had married Agnes Weller, the daughter of a farm labourer and nurse-maid to the Gill children, and when he returned to her following the armistice, the war was not left behind. He took up his stone carving tools and in the following years was employed cutting hundreds of names into stone memorials in towns and villages through the country. The war memorial in Ditchling is a simple column of Portland stone designed by Gill to stand on a patch of grass at the western entrance to the village. It was unveiled in August 1920 and is likely to have been one of the first of several Sussex war memorials that Joseph worked on.

Thanks to the 1921 census we now know that he was away from home at Great Dunmow in Essex in June of 1921. It tells us that (Herbert) Joseph Cribb was lodging at 2 Olive View, New Street, Great Dunmow with 29-year-old Arthur Smith, a cooper at the Dunmow Brewery and his wife Florence - perhaps the two men found time to swap wartime experiences. It is touching to read that Joseph was accompanied by this young wife Agnes, not wanting to be parted again, with their 10-month-old son Peter, born in Ditchling the previous year.

The Dunmow memorial was dedicated by the Bishop of Chelmsford on 17th July 1921. Gill is often credited with both design and inscriptional work on the memorials but, in this case, Joseph is named as cutting the 85 names and the 1921 census is evidence that he was in Great Dunmow shortly before the dedication. Gill meanwhile was working on another commission, the Memorial Arch at Clifton College in Bristol where the census shows Eric Gill as a visitor at the home of his friend Desmond Chute. Meanwhile, Gill’s wife Mary Ethel was at home in Ditchling with eight children, four of her own and four of her neighbours!

The 1921 census also tells us that Joseph’s workplace was ‘St Peter’s’, on Ditchling Common, a mile from the village. This was one of the wooden WWI huts widely erected as homes or workshops at the end of the war. Several of the buildings were acquired for the Catholic Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic established in 1920 by Gill, Desmond Chute and the hand-printer Hilary Pepler with Joseph as a founding member. From the 1921 census we know that Pepler at ‘Fragbarrow’, was the only Guild member present on the Common that summer but by the end of the year and ready to celebrate Christmas he was re-joined by the Gill and Cribb families. George Maxwell, listed in the census as a motor car body maker for Wolseley in Birmingham later became the master carpenter at the Guild and the artist and poet David Jones, living with his parents in Brockley at the time of the census and attending Westminster Art College, had joined the Guild by the end of the year.

Eric Gill left Ditchling in 1924 but Joseph remained at his stone-carver’s workshop becoming a mainstay of the community. In 1945 he carved 13 more names on the Ditchling War memorial and returned to Great Dunmow to add the 25 men lost in WWII. Joseph died in 1967 on his way to work and is buried in St Margaret’s churchyard, Ditchling overlooking the war memorial, where his own headstone is inscribed by his assistant in the carver’s workshop, Kenneth Eager.